This post is also available in: Spanish

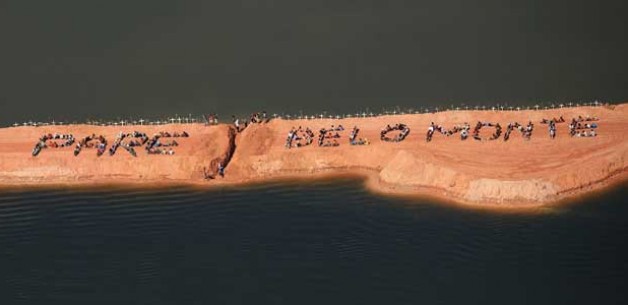

Photo credit: Atossa Soltani/ Amazon Watch/ Spectral Q

Mayalú Txucarramãe and Patricia Gualinga engaged an audience of civil society members, including BIC, in their discussion on Wednesday of women’s role in the struggles of indigenous communities to protect their lands, their rights, and their way of life from destructive infrastructure and extractive projects in the Amazon. Amazon Watch hosted the talk “The Role of Women’s Leadership in Amazonian Indigenous Struggles” this week as part of its fall 2013 Green-Bag Lunch series in Washington, DC.

Mayalú, of the Kayapó people in Brazil, discussed women’s leadership in the ongoing struggle to stop construction of the Belo Monte Dam, which is having devastating consequences on the environment and Brazilian communities. Patricia, of the Kichwa people of Sarayaku in Ecuador, told the story of success and of women’s perseverance in a decade-long fight to expel the oil corporations exploiting their territory.

Belo Monte – Mayalú’s Story:

Belo Monte is a hydroelectric complex being built on the Xingu River, one of the Amazon’s major tributaries. The construction of the dam will displace over 20,000 people, directly impact huge areas of rainforest, and put the survival of 1,000 indigenous people who depend on the river at risk. The Brazilian National Development Bank (BNDES) has committed 80% of funds for the project, and in 2012 BNDES approved the largest loan in its history (over US$10 billion) to Belo Monte, despite its commitment to withhold funds until basic social and environmental requirements for the project had been met.

While the government claims that Belo Monte will provide “clean energy,” Mayalú said, this is “clean energy that kills and destroys and leaves people without their lands and kills the history of many generations.”

“Our families have been displaced, they lost everything, and some of them never got any compensation,” she said.

Indigenous communities are fighting back, however, with greater leadership by women than in the past. Nineteen civil lawsuits have been filed and nine occupations of project area have taken place in the past year, some of which have resulted in short-term injunctions temporarily halting work on Belo Monte. Although 30% of project works have been completed, Belo Monte is one year behind schedule and $1 billion over budget, in large part due to civil society resistance.

Indigenous women have left their homes and their children, or have taken their children with them to the occupation as part of the struggle, according to Mayalú. “This is only the beginning of Kayapó women joining the fight,” Mayalú said. “Now that [men] are listening more to us, it’s a historic moment … As a women, I won’t let that go because I want to be the voice of women for my people.”

Sarayaku – Patricia’s Story:

Over a decade ago, the Ecuadorian government opened the Sarayaku territory to oil exploration without consulting the indigenous people who lived there. Patricia’s community of approximately 1,200 people first found out about the project when helicopters and men with guns landed in their territory. The Kichwa people, however, confronted the situation, building a network of national and international alliances and filming an award-winning documentary. After a ten-year struggle, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights ruled in 2012 that the government must hold consultations with project-affected indigenous peoples and that it pay reparations to Sarayaku for physical and moral damages.

“It has turned into an example that fighting and defending territory is possible,” Patricia said.

In large part, the participation of women made Sarayaku successful. “The whole position against oil corporations in our territory came out of women,” Patricia said. “When women actively participate, we end up with better decisions for the wellbeing of the community.”

Sarayaku’s fight is not over, however. The government of Ecuador, despite the Inter-American Court of Human Rights’ ruling, has yet to pay reparations or to remove the underground explosives that remain in Sarayaku. Furthermore, the government recently opened an 11th round of oil contracting in large swaths of indigenous territory in the Ecuadorian Amazon.

Patricia hopes to inspire other communities to fight for their territory and their rights as the Kichwa people have. “If a community makes itself strong, the government won’t get involved,” she said. “It’s a latent fight that is going to be very strong.”